For decades, the remains of a formerly iconic structure from Youngstown’s Central Square sat decaying off U.S. Route 422 in Girard. The roof was long gone and the windows boarded shut. Only two sculptured tiles, each depicting an open book next to a lamp of knowledge, gave any indication to the uninitiated as to the building’s one-time use.

However, for those of a certain generation, it would’ve been instantly recognizable.

The small building served Youngstown as the Central Square Library for over 30 years. A product of the Progressive Era, the branch emerged from the efforts of Joseph Wheeler, a distinguished graduate of the New York State Library School in Albany.

Wheeler was appointed acting librarian in 1915. In 1916, he helped open an early branch library inside the arcade of the Hippodrome Theater, a popular downtown vaudeville house. The small library consisted of two double bookcases behind glass doors. The station remained open from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and attracted numerous patrons coming from the evening vaudeville shows. The main library replenished the 1,200 books at the branch daily.

By 1919, demand at the Hippodrome Branch had grown too large for the arcade to accommodate any further growth. Wheeler soon struck a deal with the Youngstown Municipal Railway Co. to use a portion of a sheet steel waiting station, built to shelter patrons waiting for the trolley, to house a small Central Square Branch. Dubbed the ‘Tin Library,” it soon attracted a steady stream of patrons from around the “Diamond,” as the center of downtown was often referred to in those days.

The Tin Library held approximately 2,000 books and was heated by a small stove. Library trucks often made several trips a day in order to restock the branch’s inventory. At its peak, circulation reached over 70,000 volumes a year. In 1922, during a bid to “clean off the Square,” Mayor George Oles called for the removal of the homely structure. The library reported in 1923 that 75,000 fewer books were circulated in the year after the closing of the Tin Library.

Public outcry and Wheeler’s redoubled efforts led to a new proposal to construct a library on Central Square in 1923. The library association proposed building a structure 35 feet in length on the site of the then nonfunctional “Maid of the Mist,” a fountain located on the north side of the square. Two main reasons were advanced for building a new branch: to beautify the square and to provide a more convenient location for workers to borrow books. Libraries were increasingly seen as tools in the Americanization process as well. And many city leaders, infused with ideals from the Progressive movement, now encouraged laborers to educate themselves.

“The big [main] library building frightens some people away, especially foreign born people, or working men in their overalls, who have a perfect right to use books but are afraid to ask for them,” said Herman Ritter, chairman of the Retail Board of the Chamber of Commerce. “These are the people who should be encouraged to read, for they are full of ambition that we can well use in the development of Youngstown.”

Wheeler defended his project by claiming that the new branch would save workers valuable commute time. “The people won’t come up on the hill,” he explained, referring to the distance to the main library from Central Square. “It isn’t because they don’t want to. Most everybody here works, and losing half or three quarters of an hour on their way home to Rayen Avenue to select a book is a big item in a worker’s day.”

Politicians and some other prominent businessmen emphasized different reasons for approving the project. “My chief reason for approving the plan, however, is the greatly improved appearance it will give the Diamond,” former Youngstown Mayor Carroll Thornton exclaimed. A new library downtown would “serve to remind visitors that Youngstown is interested in books as well as dollars,” said A.E. Adams, president of First National Bank.

Not everyone in the business community agreed. E.C. McMahon, owner of a piano company on East Federal Street, opposed plans for the library, stating that Central Square should be reconstructed to more adequately reroute traffic through the center of downtown. He complained that the branch library would make that too difficult, thus hurting business on the east end of downtown.

But such voices were in the minority, especially when library officials explained that the building could be constructed at no cost to taxpayers and that it was intended to be easily movable – in case planners sought to redesign Central Square in the future.

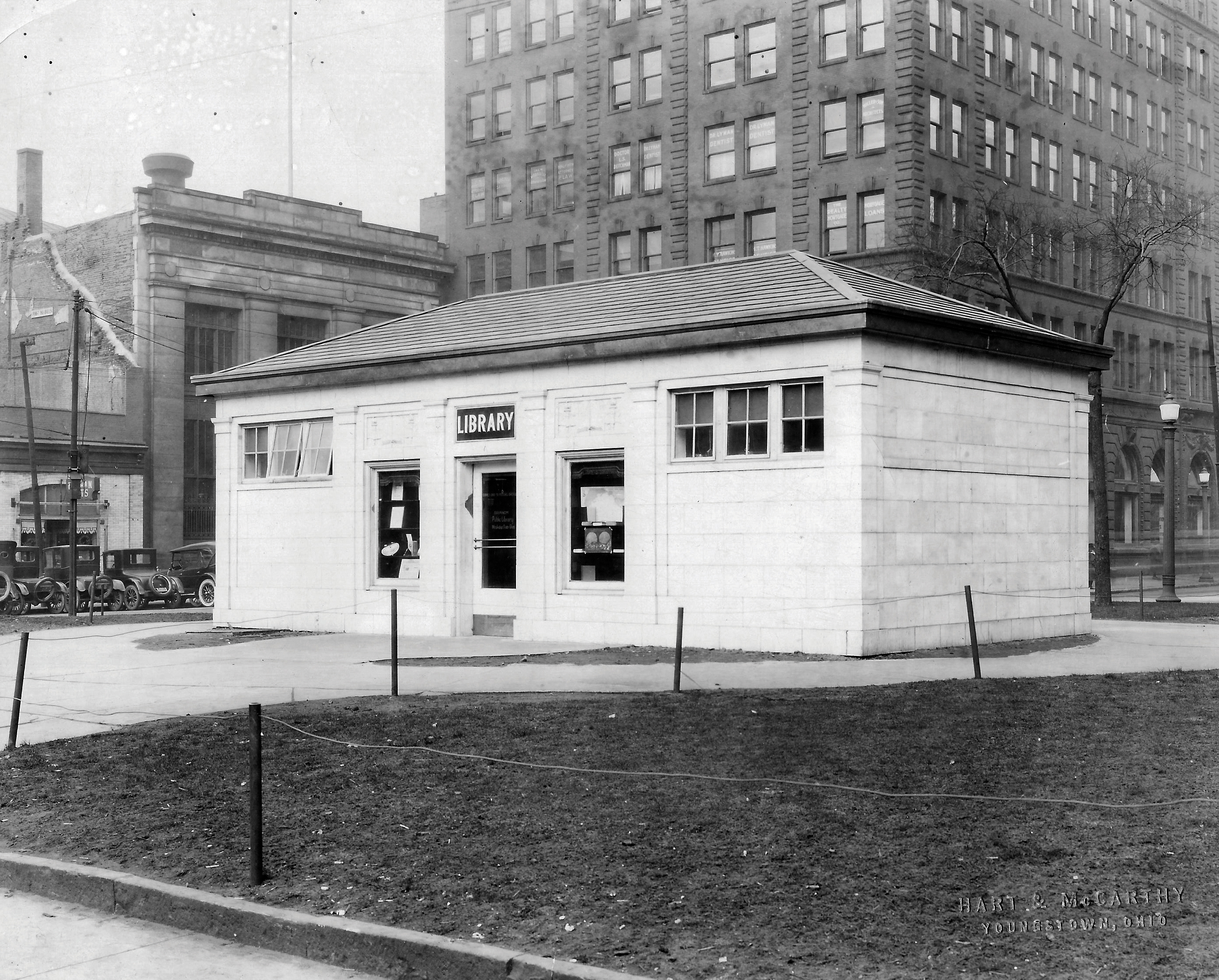

All materials and labor were donated by local contractors or paid for with donations, and work on the $10,000 structure began in the early fall of 1923. The green tile roof and white-glazed terra cotta building was meant to resemble the Butler Institute of American Art. The walls of the well-built precast shell were 18 inches thick. The building’s height was capped at 14 feet to avoid blocking views from either the north or south.

Lights were placed under the eaves to broadly illuminate the library, which the Youngstown Vindicator soon described as “the outstanding feature of our public square.” The lighting made the library highly visible at night without obscuring its architectural details. The branch formally opened on Dec. 8, 1923.

The library held 5,000 volumes. Unlike the branch in the Hippodrome, most of the books covered technical subjects, business and other works of nonfiction. Patrons could reserve books from the main library and have them sent to Central Square as part of two daily deliveries. Like the former Hippodrome Branch, it operated from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week.

The branch boomed along with downtown during the Roaring Twenties. At that time much of retail and civic life was centered in the central business district. “All the lodges and clubs were downtown,” Youngstown resident Edward Manning later recalled. “The doctors, dentists and lawyers were all downtown. A good many of the churches were on Wood Street or in the downtown section.”

The opening of more branches throughout the city, especially the opening of the new South Side Library in 1929, affected circulation at the Central Square Branch. However, its numbers soon rebounded and continued to grow – even during the height of the Great Depression. In 1939, circulation numbers at Central Square were higher than at any other branch in the county, with the exceptions of the Struthers and South Side libraries.

Mechanical books, heavily featured at the Central Square Branch, led in circulation during the latter part of the Great Depression. Books on foreign countries where American troops were stationed during World War II proved popular during the 1940s, according to library reports.

By the early 1950s, the city once again began discussing the possible reconfiguration of Central Square. Proposals were put forward to move both the library and the much beloved Civil War memorial, known popularly as the “Man on the Monument,” from the islands downtown. Keeping Central Square beautiful now took a backseat to the need to ease traffic congestion downtown. In 1953, a precipitous drop in funding for the library system, and a decline in circulation of 1,463 books at the Central Square Branch, caused the eventual closing of the library in 1954. Throughout its life, the little library circulated well in excess of two million books.

The building was sold to Boccia Construction and Demolition Co. of Niles, and after three decades, one of the public library’s most successful experiments came to an end. Countless workers and newly arrived immigrants were exposed to new worlds through the literature distributed by the Central Square Library. And long after the “Diamond” became refashioned as Federal Plaza, memories of the library and old Central Square remained a fond memory in the minds of generations of Youngstowners.

© 2018 Metro Monthly. All rights reserved.

Nice piece, Sean. Joseph Wheeler’s son, John Archibald Wheeler, became a prominent physicist and doctoral advisor to Kip Thorne, the most recent winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics.

www.science20.com…

I really enjoyed this piece of fascinating history. Having been born and raised here, I’m ashamed to say that I only first became aware of the central square library when I attended one of Mark Peyko’s downtown walking tours.