Groundbreaking “Youngstown 2010” marks 10th anniversary. Weighing the landmark plan’s legacy, impact. From the archives.

For years, the city of Youngstown continued to plan for growth even as the metropolitan area rapidly suburbanizied. The decline of the once vaunted local steel industry in the 1970s pushed the rudderless city into uncharted waters. With a continuously shrinking population and a crippled economy, Youngstown entered the ranks of the country’s most distressed urban areas. As civic morale hit its lowest point, a new idea came to the fore. After years of attempting to plan for growth, the city would violate traditional notions of urban planning: Youngstown decided to accept and plan for shrinkage.

The genesis of what became the most talked about planning initiative in the country dates back to before 2002. “It could go back to when Council and John Swierz led an effort to reserve money for a new plan,” former Youngstown City Planner Anthony Kobak remembered. “Some members of Council went to Chattanooga, Tenn., which had recently completed a plan that got a lot of publicity. They then realized that Youngstown should update its comprehensive plan.”

Along with the guidance of Urban Strategies Inc. of Toronto, Canada, the city held a series of stakeholders meetings to help construct the first citywide plan since 1974. Jay Williams, then Community Development Agency director; William D’Avignon, deputy planning director; Anthony Kobak, project manager; and Hunter Morrison, director of Urban and Regional Studies at Youngstown State University, all played key roles early in the process.

According to Kobak, “The shrinking city concept wasn’t in anyone’s mind yet, and that’s a good thing. You go into a planning process not knowing what the vision will be. You have some ideas, but you don’t want to sway the process.”

In December 2002, nearly 1,400 citizens descended on Stambaugh Auditorium to attend a “public vision” meeting held by the city. By the next year, volunteer committees and sub-committees went to work on neighborhood property surveys and various aspects of what became known as the “Youngstown 2010 Plan.”

In July 2005, the city of Youngstown formally adopted the “Youngstown 2010 Plan” as the city’s guiding vision for the future. Within a very short period of time, a city known primarily for mismanagement and organized-crime connections became the destination for anyone interested in turning around America’s shrinking cities.

The American Planning Association recognized the plan in 2006 with the ‘National Planning Excellence Award for Community Outreach,’ and “Youngstown 2010” made The New York Times’ ‘Sixth Annual Year in Ideas’ list. Media outlets from Europe to Japan descended on Youngstown to see what PBS called “The Incredible Shrinking City.”

In recent years the spotlight put on “Youngstown 2010” has faded. Where is the city 10 years later, and what is the legacy of the plan today?

The “Youngstown 2010” “Vision” accepted that Youngstown had become a smaller city. It called for a redefining of the city’s role in northeast Ohio’s economy. Improving the quality of life and the area’s local and national image occupied a central position in the vision; and “Youngstown 2010,” unlike other previous plans, called for widespread community involvement.

The nearly three-year-long envisioning process produced several planning “themes” which have seen a mixture of successes, failures and unrealized possibilities.

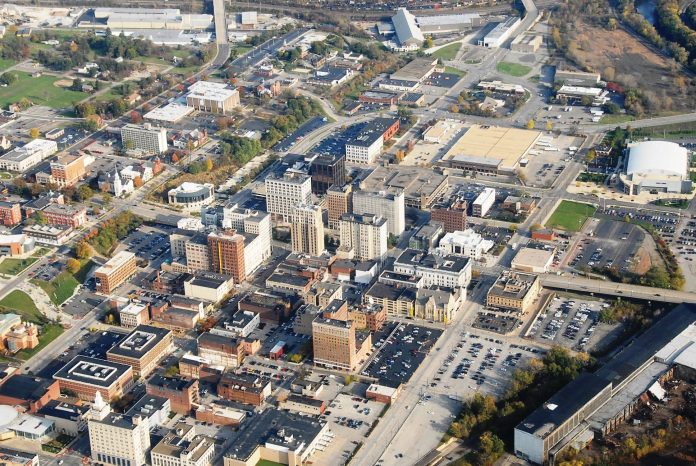

A key theme emphasized returning vibrancy to a distressed downtown. The last decade witnessed a miniature renaissance, as the building of the Chevrolet Center (now the Covelli Center) and the creation of the downtown entertainment district helped spawn a collection of bars, restaurants and clubs in the once desolate central business district. New residential development also occurred downtown. In 2015, the downtown received its first plan in years, something “Youngstown 2010” specifically called for.

A partnership between the city and Youngstown State University helped finally open a direct connection with the downtown via the construction of the Williamson College of Business Administration. The university’s Centennial Campus Master Plan states that it was “developed within the framework of ‘Youngstown 2010.’ ”

After much talk, the city obtained a new zoning code, thanks primarily to “Youngstown 2010.” “The plan called for making various changes to land use and said that we should adopt a new zoning ordinance,” Community Development Agency Director William D’Avignon remembered. “This is only the third time in the history of the city that there’s been a complete revamping of the city zoning ordinance.”

Calling for the creation of a “green network” throughout the city is one of the more unique parts of the plan. An early success involved obtaining a Clean Ohio grant to enable the purchase and reclaim 200 underdeveloped acres next to Lincoln Park on the East Side.

A hike-bike trail that takes advantage of the underutilized waterfront and connects to Mill Creek Park and the university is mentioned as a possibility in the plan. Linking the park to Market Street through rapidly depopulating streets like Falls Avenue on the South Side has also yet to happen, although some streets like Old Furnace, which connected to Glenwood, are now partially closed off and returning to nature. However, the call to “green” Youngstown helped inspired a variety of environmental activists.

Attorney Debra Weaver helped launch the “Grey to Green Festival,” an environmentally friendly festival dedicated to promoting the greening and revitalization of Youngstown. “Grey to Green” ran for five years straight and featured guests like Will Allen, one of the country’s most prominent urban farmers.

“The idea sprang directly from having read that plan,” Weaver said. “The whole idea behind it was to get everyone on board doing something with the land and community. And though I don’t think the greening of the city is moving as fast it should be, I am amazed at the numbers of gardens popping up in vacant lots and side yards throughout the neighborhoods.”

Creating competitive industrial districts has met with some success, but traditional heavy industry brought the city’s largest economic coup in years with the nearly $1 billion expansion of the Vallourec Star pipe mill on U.S. Route 422.

Locating a National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute in the city garnered numerous headlines for the area and a mention in President Obama’s State of the Union address two years straight. Many hope it might eventually jump-start the local economy in years to come.

Yet Youngstown’s overall economy remains weak; the city has not returned to pre-recession employment levels. Youngstown’s economic role in the region remains very much ill defined, and that failure serves as one of the most unrealized parts of “2010.”

Youngstown’s progress in creating “viable neighborhoods,” a central theme of the plan, is also mixed. As the downtown core continues to strengthen, the city’s neighborhoods continue to experience high levels of vacancy. This process revealed itself in 2011, when Youngstown registered an 18 percent population drop in the decennial census—the largest decline in city history.

In 2009, the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation (YNDC) formed to fill the need for a capable neighborhood community development organization. At that point, the Garden District and Idora neighborhood plans were both complete, but progress stalled after the city’s chief planner resigned and was not replaced.

“The city was to begin doing neighborhood plans after the ‘2010 Plan’ was completed and adopted,” said Ian Beniston, executive director of the YNDC. Beniston helped develop one of the first neighborhood plans for the Idora area.

“I doubt there would be any Idora neighborhood plan if there had never been a ‘2010 Plan,’ ” Beniston stated. “ But ‘a call to action,’ that part of the ‘2010’ vision, is what we are really about here—moving beyond the planning to actual concrete results.”

The YNDC began contracting with Youngstown in 2013 to provide neighborhood-planning services. They currently have action teams working on plans in Powerstown, Lincoln Knolls, Brownlee Woods, Crandall Park and the Garden District.

In 2014, YNDC released a “neighborhood conditions report” with updated information from the 2010 Census. However, they caution that the report “is an important tool for policy and planning decisions, but it is not a strategy within itself.”

Dr. John Russo, former coordinator of the Labor Studies Program at the Williamson College of Business Administration and co-director of the Center for Working-Class Studies at Youngstown State University, has extensively studied and written about the plan and the post-planning process.

“The ‘2010 Plan’ was about hope and providing a certain type of goal, but was there ever any real interest in implementing it? I would say there wasn’t, other than the marketing and economic developments of it,” Russo said. “When you gather all that community support and nothing happens, there emerges a very deep sense of betrayal in the neighborhoods. And I think that hurts everyone.”

The year 2010 didn’t signify the end of the comprehensive plan, merely a date that coincided with the decennial census. “Youngstown 2010” was meant to serve as “a guide for the community and future city administrators to follow and implement,” according to the plan. But it remains unclear if any mayor since Jay Williams has embraced the plan as an overall strategy. The legacy and future of the plan today remains a contested one, even as the spirit of “Youngstown 2010” continues to inspire local community activists and neighborhood planners.

Metro Monthly is a local news and events magazine based in Youngstown, Ohio. We circulate throughout the Mahoning Valley (and beyond) with print, online and flipbook editions. Be sure to visit our website for news, features, restaurants, local history and essential Valley events. We offer print and website advertising. Office: 330-259-0435.

© 2015 Metro Monthly. All rights reserved.